The Sömmerda Camp Diaries

One of the subcamps of the Buchenwald concentration camp was located in Sömmerda, Thüringia, where 1,300 Hungarian Jewish women were deported in September 1944. Some of the women began to create and write diaries, an activity that developed into part of a lively cultural life. While it was not uncommon for prisoners to create opportunities for creative forms of expression as part of the strategy for spiritual survival in a context of scarce resources, it is perhaps unique in the history of the Holocaust, not only in Hungary but also in Europe, that a diary-writing community should leave behind 29 small books of their own making. Despite their historical value, the Sömmerda camp diaries are mainly unknown. This virtual exhibition aims to help eradicate this ignorance.

The under-representation of the history of the Holocaust in Hungary may be observed not only by those who follow the international historiographical discourse and browse through the published books and sources, but also by those who visit the exhibitions of Holocaust museums and memorial sites around the world. There are many reasons why Hungary, the country in Europe from where the third most victims died in the Holocaust, has not received the attention it deserves in relation to its tragic historical weight. The long-standing Western European dominance of Holocaust discourse, the linguistic barriers to understanding Hungarian sources for non-Hungarian-speaking researchers, and the belated and partial integration of Hungarian research into international trends have all contributed to this.

In Europe, geographically asymmetrical knowledge of the Holocaust has developed. The vast majority of victims, around 90%, were Jews from Eastern and Central Europe. Almost all of the key sites of mass murder (with the exception of places such as Dachau, Mauthausen, and Bergen-Belsen), where tens or even hundreds of thousands of Jewish victims died, are located in Eastern Europe. Yet much more is known about the persecution of Jews in Western Europe.

At the heart of the image of the Holocaust in Western Europe is Auschwitz-Birkenau, which was not only a death camp but also a forced labor camp, whose survivors were largely Western European Jews. After the Second World War, survivors on this side of the Iron Curtain were free to write and publish, unlike survivors in Eastern Europe who, in addition to being silenced by their traumas, suffered repression and censorship by the Communist regime.

Following the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem in 1961 and the monographic work of Raul Hilberg, the “Holocaust” was defined as the systematic, industrialized genocide of Jews. Over the last three decades, Auschwitz has become “the symbol of the Holocaust.” Auschwitz-Birkenau operated with the highest mortality rate in the spring and summer of 1944, when Hungarian transports were rolled onto the ramps built to receive that country’s citizens. In the first third of 1944, the camp murdered around 6,000 people a month. However, between mid-May and mid-July, at least 300,000 Hungarian Jews died in Birkenau. Every third victim of the mass murders committed in the camp complex was deported from Hungary. The record speed with which the Final Solution was implemented in Hungary made Auschwitz what we know it as today: the “capital of the Holocaust,” a symbol of modern, industrial mass murder.

The photographs in the world-renowned Auschwitz Album visually capture and tell the story of the journey from the ramp to the gas chambers, portraying the journey as the SS officer who took the photographs wanted to present it. At the same time, the album locates Hungarian Jewry in the universal role of Auschwitz victims. In the photographs included in the Auschwitz Album, we see not only some of the women and men who were sent to the gas chambers but also men and women who were disinfected, depilated, stripped of their clothes, and selected for work.

Hungarian historiography largely portrays the Holocaust in Hungary as an administrative story of the road to deportation: the deprivation of rights, property, personal freedom, and ultimately, life. Despite the extensive historiography surrounding this topic, less is known about what happened to those who survived the selection. The history of the hundreds of forced labor camps that operated in 1944-45 is much less researched. Nevertheless, when survivors began to speak out in the 1990s, they were asked more often about Auschwitz than about the other camps. The structured series of questions in the Shoah Foundation's video archive, the most extensive collection of video testimonies, was aimed at creating a record of a “shared memory.” The unknown subcamps did not fit into this picture. The result was that the survivors themselves spoke of Auschwitz: they took on the role of Auschwitz survivors, even though they had survived up to four or five other camps, death marches, and Allied air raids, and mourned the deaths of their families who had been murdered in Auschwitz. Their imagined audiences knew Auschwitz; they could resonate with experiences about it, lending credence to their story. The forced labor camps, where there were no gas chambers and crematoria and sometimes more tolerable conditions – even allowing for cultural activities – have not become part of the canon of Holocaust memory, nor were the sources produced in these places.

Over the past decades, according to British Holocaust scholar Dan Stone, “the apparent paradox of modern technology being employed in the service of mass murder” has so captured our attention that it has prevented us from seeing other aspects of the Holocaust. When Hungarian Jews were deported, not only was a new ramp built at Auschwitz, but several forced labor camps were established next to German factories. Of the 440,000 Hungarian Jews deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, roughly one in four were found fit for work, and these approximately 110,000 became the last source of labor for the German war industry. A peculiarly Hungarian phenomenon influenced the composition of the Hungarian Jews registered in Auschwitz. A large number of women of working age were put on deportation trains instead of men, the latter being prevented from being deported by the military labor service.

In July 1944, six weeks after they arrived in Auschwitz, some 2,000 women, mainly from Transcarpathia and to a lesser extent from Nagykanizsa and the surrounding area, were selected for work, including the diarists. With the arrival of the Hungarian women, the Buchenwald subcamp was established in Gelsenkirchen-Horst, which the Allies bombed on 11 September 1944. According to German and Hungarian sources, about 130 Hungarian Jewish women lost their lives, and many were seriously wounded in the bombing. Some of the survivors – a total of 1,293 women – were transported to Sömmerda in Thüringia to produce ammunition at the Rheinmetall-Borsig factory. The women forced laborers were marched out on foot on 4 April 1945. In the following weeks, the marchers were liberated by Allied troops at various locations.

Sömmerda, just one of hundreds of smaller and larger sub-camps, is unsurprisingly almost entirely unknown. The main camp alone, Buchenwald, was home to more than 130 subcamps between 1940 and 1945. What makes the camp so special is that it is the location of a unique group of sources of which we were previously unaware. The diaries are the rarest source of information on life situations and events such as genocide and persecution. Personal accounts of one of the most extreme locations associated with the Holocaust, written almost contemporaneously with the events, are perhaps far fewer in number than memoirs written decades later.

Az írni akarók nagy erőfeszítésekkel a lágerekben is megtalálták a módját annak, hogy papírhoz és ceruzához jussanak. Sömmerdát azonban a lágernaplók forréscsoportján belül is megkülönbözteti valami: mindeddig nem jutott tudomásunkra hasonló példája annak, amikor ugyanabban a táborban, ugyanabban az időben, ugyanazon fogolycsoport tagjai ilyen nagy számban naplókat írtak volna és ezek a naplók fenn is maradtak volna. A sömmerdai naplóíró közösség egyedi a maga nemében.

One of the most significant difficulties in researching the Holocaust as a global event is the multilingual nature of the sources. The canon of Holocaust literature is dominated by memoirs written in Western languages. Researchers have quoted and used these as a basis for their conclusions, making these texts central to the canonization of memory. In contrast, others are entirely excluded from the process of historical knowledge and understanding. The majority of the known diaries were written in Yiddish, Polish, and Hebrew in ghettos. The most significant of these is the Warsaw Secret Ghetto Archive, the Oneg Shabbat created by Emanuel Ringelblum, which comprises 1,680 items and 25,000 pages. We may also mention the diaries of Łodź and Vilna. The other large group of sources is the diaries written in hiding (e.g., of Anne Frank and Eva Heyman). In the Hungarian context, we can mention diaries written during military service.

Several forced labor camps similar to Sömmerda were established (such as Mühldorf, Markkleeberg, Duderstadt, and Salzwedel), where mostly or exclusively Hungarian Jewish women were employed and who, in most cases, had better chances of survival in military factories than ones located underground. According to the memoirs, conditions may have been present that would have allowed for diary writing, but no diaries have survived in such large numbers.

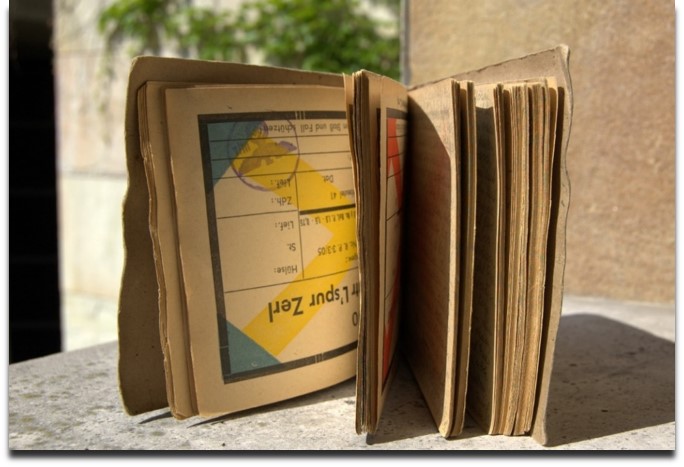

So far, we are aware of 12 diaries and 14 other small books, variously filled with poems, memoirs, camp newspaper articles, and prayers from the camp at Sömmerda. The most important archives are Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, the Museum of Hungarian Speaking Jewry (Safed, Israel), the Holocaust Memorial Centre in Budapest, and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. (The whereabouts of a further diary and two books of poetry are still unknown.)

Most of the 44 Hungarian camp diaries known so far were written in ‘privileged’ camps, such as by the Kasztner group in the Bergen-Belsen Ungarnlager and the rural Jews deported on the Strasshof transports to the Austrian family camps, who could keep their luggage and thus write on paper brought from home. However, handwritten diaries from Sömmerda have survived.

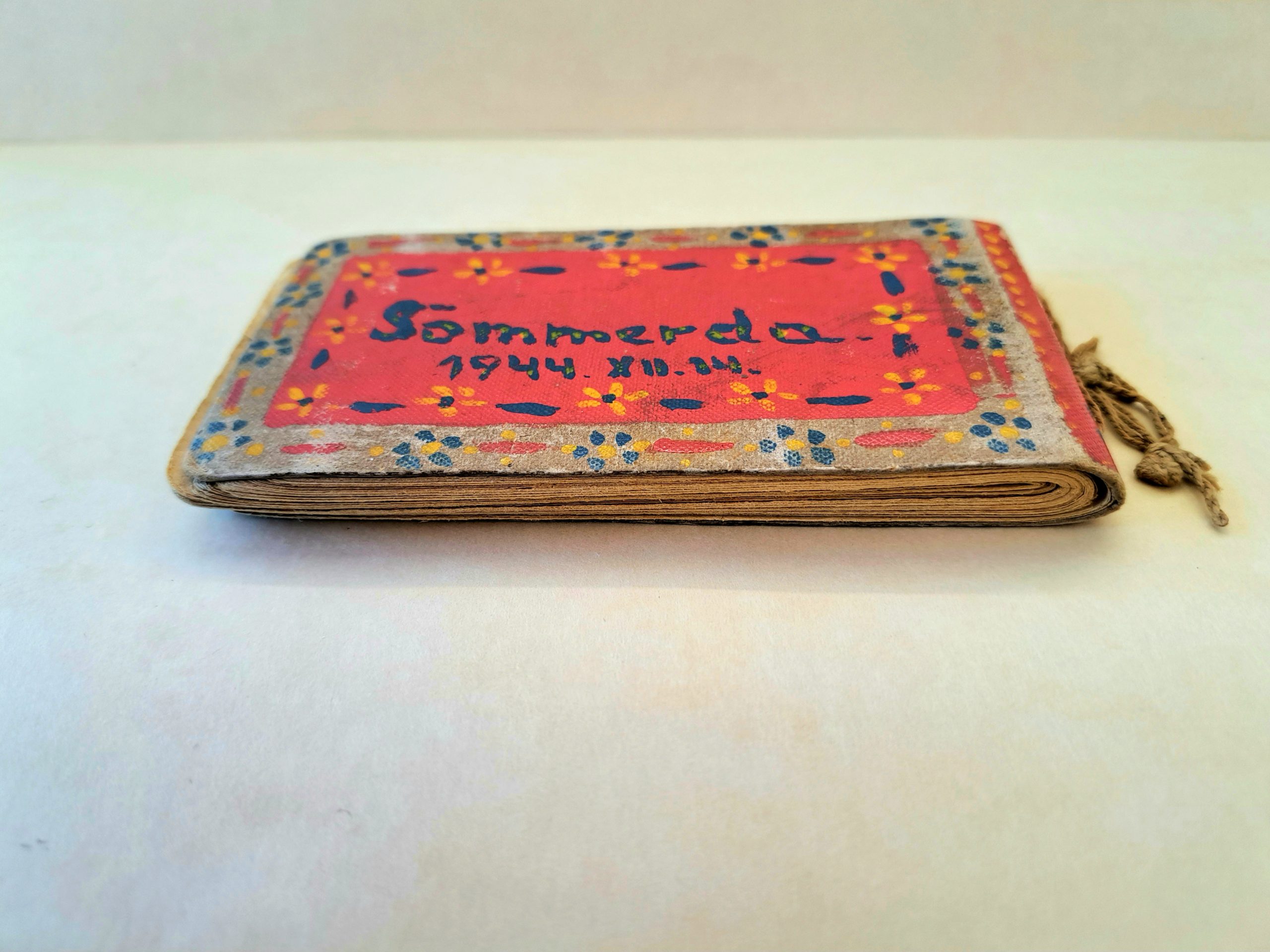

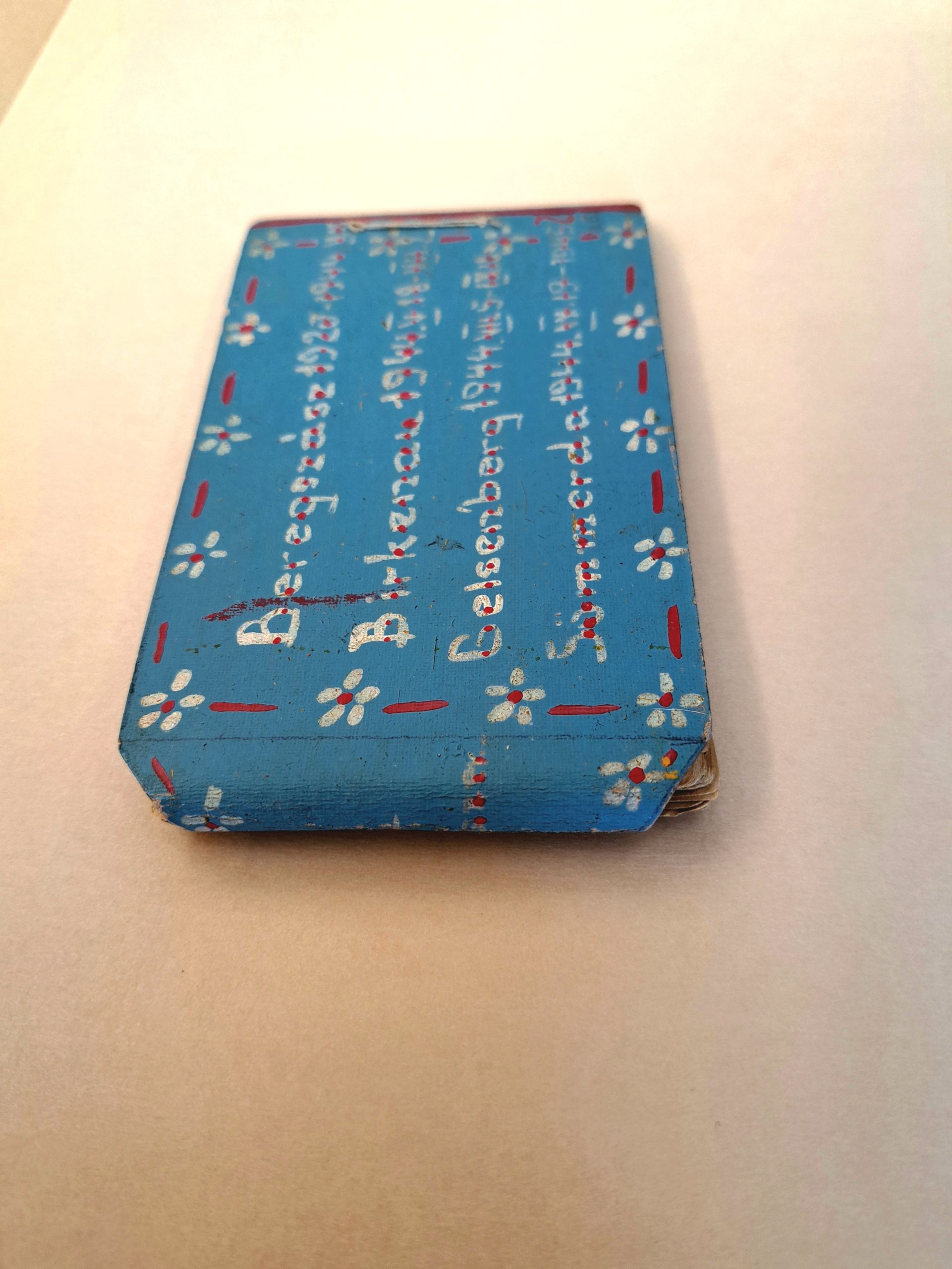

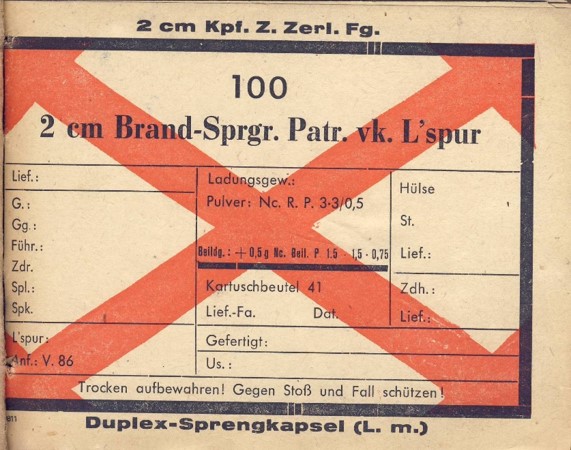

The absence of the fear of spontaneous violence and the predictable, structured daily life of factory work allowed for the development of daily activities and routines, including diary-making and diary-writing. This included the processes of sourcing materials, creating, and decorating. To make the tiny booklets in Sömmerda, the women stole labels from ammunition boxes, as well as cardboard and wires from the factory. The covers are decorated with inks originally used to mark types of ammunition. The women became a source of labor for the factory, but they turned the factory into a source of materials and tools for their diaries.

Diary writing was part of a wide range of cultural activities in the camp. Diaries not only told the story but also shaped the life of this community. The 26 small books may be associated with 19 women who owned these objects. However, the community that participated in the production of this content is much more significant if we count the authors of the memoir entries and poems together. Little books were given as gifts to one another, and poems were not only recited but also copied. Books of poems passed from hand to hand, just as the memory books did. The funny scenes in the camp newspaper were performed after they were written down. The oral and written activities of cultural life interacted.

According to the author of a handbook on diary reading, we read diaries because they often “tell us stories in ways that defy our expectations.” In many ways, this is also true of the stories in the diaries from Sömmerda, which were shaped by the particularities of deportation in Hungary, the conditions of the forced labor camp, and the social and cultural backgrounds, as well as the female roles, of the diarists. To gain a deeper understanding of this diarist community, we should heed Ruth Klüger's advice. The Austrian survivor asks the readers of her memoir to “rearrange a lot of furniture in their inner museum of the Holocaust.” These texts, therefore, also provide an opportunity to reorder the methodological toolbox of the Holocaust, including the phenomenon of diaries as sources, and to select the analytical tools that bring us closest to the inner world of their writers. „olyan történeteket mesélnek el nekünk, amelyek szembe mennek az elvárásainkkal.” Ez sok szempontból igaz a sömmerdai naplókban olvasható történetekre is, amelyeket a magyarországi deportálások sajátosságai, a kényszermunkatábor körülményei és a naplóírók társadalmi, kulturális háttere és női szerepei együttesen formáltak. Ahhoz, hogy megismerhessük és amennyire lehetséges megérthessük e naplóíró közösséget, Ruth Klüger tanácsát kell megfogadnunk. Az ausztriai túlélő arra kéri memoárja olvasóit, hogy „ rendezze át a bútorokat a holokauszt belső múzeumában”. Ezért ezek a szövegek arra is lehetőséget teremtenek, hogy a holokauszt és a naplók módszertani eszköztárát újra rendezzük és kiválasszuk azokat az elemzői eszközöket, amelyekkel legközelebb juthatunk a naplóírók belső világához.