The dozens of Hungarian-language camp diaries were primarily written by the inhabitants of the special camp section of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, the so-called Ungarnlager, by the rural Jews who were transferred from Auschwitz to various labor camps instead of the Strasshof distribution camp, and the women deported to the Buchenwald subcamp, Sömmerda.

Number of Diaries:

Strasshof (and different family camps): 13

Bergen-Belsen: 8

Sömmerda: 12 (14)

Auschwitz-Birkenau (and different subcamps): 10

Bergen-Belsen

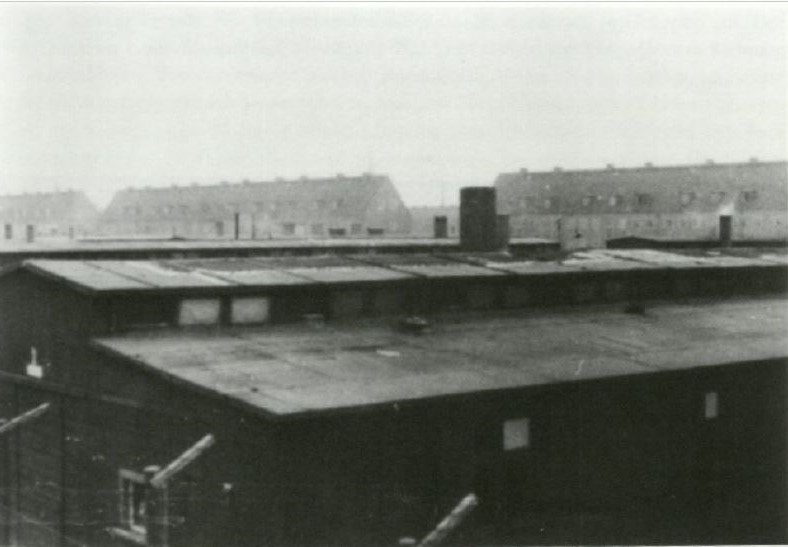

The Hungarian Camp sector of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany was the site of the so-called “Kasztner Group.” Under the terms of an agreement between the Zionist Rescue Committee, led by Rezső Kasztner, and SS leaders in Hungary, most notably Heinrich Himmler's representative, Kurt Becher, the Kasztner train departed Budapest on June 30, 1944, in exchange for a substantial sum of money and other valuables. The train initially transported approximately 1,700 passengers to a separate section of the Bergen-Belsen camp. The first group of “Kasztner Jews” crossed to neutral Switzerland in August 1944, the others in December. Historical works on the Bergen-Belsen camp, primarily in English, focus on the camp's history from the perspective of the Allied troops and as part of the British narrative of World War II. The Kasztner group, which was removed by the end of 1944, was not included in these studies. While the negotiations between the Zionist Aid and Rescue Committee, which organized the Hungarian camp, and the SS have been extensively analyzed in the literature, the nature of the life of the Kasztner Jews in the camp is little known. Conditions in Bergen-Belsen were more conducive to diary writing. The SS regarded the inhabitants of this camp sector as “hostages” or “exchange Jews,” which gave them many advantages. Members of this group were in a privileged position: families were allowed to stay with their children, they were not abused, they did not have to do forced labor, they could keep their luggage, and they had better supplies, some of which were brought from home and others provided by the SS or the Red Cross. In addition, limited autonomy was established within the camp under the control of the Hungarian Jewish camp leadership, which divided up positions and resources among its members, leading to numerous conflicts. The community was divided by several internal fault lines, partly shaped by pre-war social, religious, and ideological differences. The diaries report on this complex situation through the filter of actors thinking in terms of a variety of group interests. In addition, another diary was created in the women's prison camp of Bergen-Belsen, where deportees were deported without any privileges and where starving prisoners suffering from typhus epidemics waited in overcrowded barracks for the arrival of British-Canadian troops in April 1945.

Transports from Strasshof

The second major group of diaries is associated with the persecuted people who were sent to labor camps in Austria in the summer of 1944. During the period of mass deportations, some trains bypassed Auschwitz-Birkenau. At the end of June, approximately 10,000 to 15,000 people from several Hungarian towns, including Szolnok, Szeged, Debrecen, Békéscsaba, and Baja, arrived in the Strasshof area of Austria. The background to this affair, which remains unclear, may have been the intention to alleviate the labor shortage in Austria, Eichmann's “blood for goods” campaign, and negotiations with the Allies. The Jewish families thus concerned were dispersed from the Strasshof distribution camp to the surrounding villages and towns. Most of them were employed in agricultural work, while some were involved in rubble clearance and the construction of anti-aircraft installations. There was no selection, and families were generally allowed to stay together. Many died as a result of inadequate care and disease, as well as the cruelty of some members of the SS, but even so, more than 80 percent of the Hungarian Jews who were sent to Strasshof survived the war.

Sömmerda

The third group of diarists did not escape Auschwitz-Birkenau, where roughly one in four of the 440,000 Hungarian Jews were found fit for work, and these approximately 110,000 became the last source of labor for the German war industry. In July 1944, six weeks after they arrived at Auschwitz, some 2,000 women, mainly from Transcarpathia and to a lesser extent from Nagykanizsa, were selected for work, including the diarists. With the arrival of the Hungarian women, the Buchenwald subcamp was established in Gelsenkirchen-Horst, which the Allies bombed on 11 September 1944. Some of the survivors – a total of 1,300 women – were transported to Sömmerda in Thüringia to make munitions at the Rheinmetall-Borsig factory. The SS evacuated the camp on 4 April 1945. In the following weeks, the Allied troops liberated the marchers at various locations. The women forced laborers had a lively cultural life, which included the production and writing of diaries. The diary-writing community in Sömmerda has thus created a unique group of sources in the European history of the Holocaust.